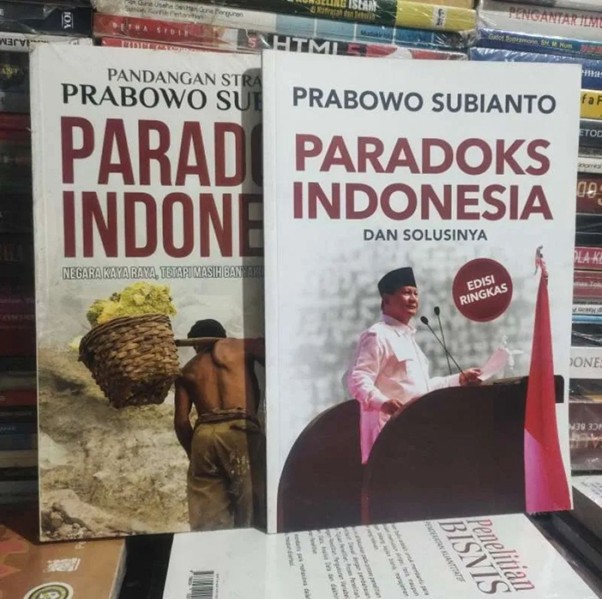

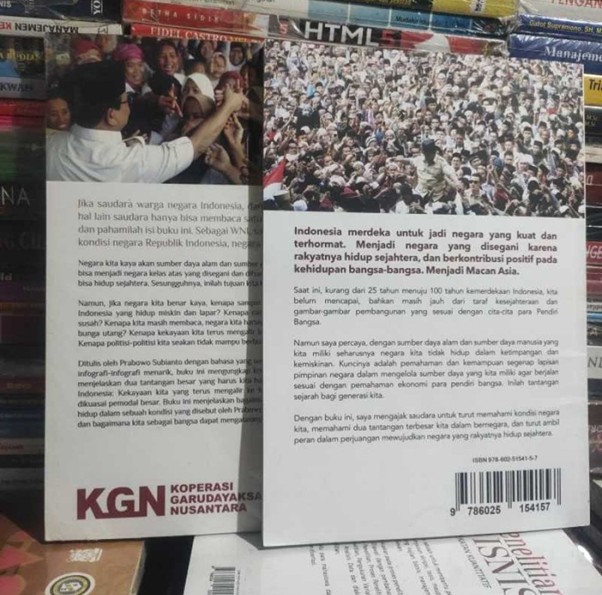

In his groundbreaking book *Paradoks Indonesia*, Prabowo Subianto presents a stark contradiction: a nation rich in natural and strategic resources, yet plagued by persistent poverty, inequality, and disempowerment. While the book primarily discusses macroeconomic and geopolitical issues, its core argument resonates deeply within the infrastructure sector, especially in the aviation ecosystem, where Indonesia has developed an impressive network of airports but has not yet fully turned them into tools for widespread prosperity.

Currently, Indonesia operates over 300 airports. Many, particularly in major cities, have undergone significant transformations, featuring modern terminals, digital systems, and rising international traffic. However, beneath this progress lies a critical question: Who truly benefits from airport development?

Beyond Runways and Revenues: Rethinking Airport Purpose

Most airport development has been viewed through metrics like passenger numbers, airline connectivity, and non-aeronautical revenue. While these are helpful indicators of performance, they do little to show whether airport growth promotes keadilan sosial—social justice.

We need to start rethinking airports not just as commercial assets or government-run entities but as platforms for social benefit. The principle of bandara untuk rakyat—airports for the people—should guide both policy and operations. This means making sure that the economic activities around airports are accessible not only to big businesses or foreign investors but also to local communities, SMEs, and cooperatives.

Unlocking Community Participation in Airport Economies

Local people living in proximity to airports are often spectators to a spectacle of aviation progress. Fences separate them not just physically, but also economically. While duty-free stores, executive lounges, and high-end F&B chains flourish inside terminals, informal vendors, local artisans, and service providers remain outside the gate, quite literally and figuratively.

This exclusion can be reversed by intentionally creating pathways for people to participate in the airport economy:

- Structured SME Integration: Allocate dedicated zones within terminal spaces or arrival halls for curated local SMEs, cooperatives, and community businesses, providing them with training, brand support, and quality control mechanisms.

- Service-Based Micro-Entrepreneurship: Rethink roles such as passenger & baggage handling, airport guides, catering providers, or eco-cleaners as avenues for inclusive economic participation, with support from local governments and vocational training centres.

- Community-Run Logistics and Last-Mile Services: Facilitate the inclusion of local cooperatives in airport logistics, including last-mile cargo, warehousing, or fresh produce supply chains to the airport ecosystem.

- Tourism and Cultural Integration: Airports, especially in tourism gateways like Labuan Bajo or Yogyakarta, should act as direct bridges to local culture. Community-based tourism providers, handicraft clusters, and local culinary brands can be uplifted with infrastructure, digital platforms, and policy incentives.

The Role of Government: From Regulator to Empowerer

To operationalize people-centred airport management, the government must go beyond its traditional role as regulator and become an enabler. This requires:

- Incentive Schemes: Through the Ministry of Transportation and the Ministry of Cooperatives, provide tax relief, rent subsidies, or access-to-finance programs for verified community-run airport enterprises.

- Public Procurement Reform: Require a certain percentage of airport procurement (non-aeronautical services) to be sourced from local or cooperative entities.

- Airport Operator Mandates: BUMN and BUMD airport operators must be mandated to include inclusive economic participation as part of their KPIs.

- Legal Safeguards and Standards: Ensure that while inclusion is expanded, safety, security, and service quality are upheld through training and accreditation.

This approach aligns with Prabowo’s focus on kedaulatan ekonomi nasional — not just protecting the nation from external threats but developing it from within through empowerment. of the smallest economic actors.

Airports in Remote Areas: Beyond Commercial Viability

A key aspect of Paradoks Indonesia is the neglect of outer regions. The same paradox applies to aviation: airports in remote areas are often deemed financially unviable, but socially critical. These airports connect communities to healthcare, education, commerce, and administrative services.

Instead of letting them languish, these airfields can be revitalized through:

- Multi-purpose usage (health, disaster response, logistics)

- Public Service Obligation (PSO) schemes with social impact KPIs

- Community-based airport stewardship models in partnership with local governments

Environmental and Social Sustainability

Equity must also be matched with sustainability. As airports expand, environmental impacts — from noise pollution to carbon emissions — affect nearby populations. A socially just airport is also a green and accountable one.

This calls for:

- Community consultations in airport master planning

- Green Airport Initiatives (solar energy, waste management) involving local employment

- Noise compensation funds and housing rehabilitation for impacted residents

Conclusion: Rewriting the Social Contract of Aviation

Indonesia’s aviation sector stands at a crossroads. It can continue the current path — prioritizing speed, scale, and profit — or it can choose to humanize the system. The real take-off will occur not when more aircraft land at our airports, but when more livelihoods are lifted through them.

As Prabowo reminds us, “Indonesia is rich, but its people are still many in hardship.” Let our airports be more than steel and concrete; let them be gateways not just to the sky, but to a better life — accessible, inclusive, and dignified for all.