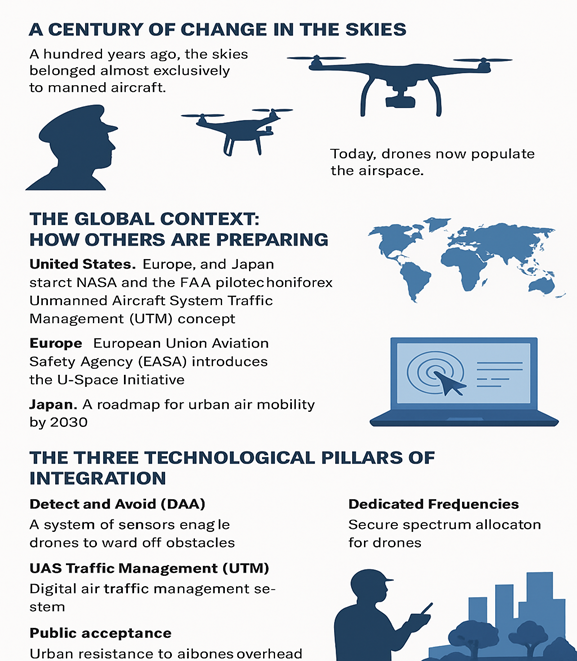

A Century of Change in the Skies

A hundred years ago, the skies were a relatively simple space. They belonged almost exclusively to manned aircraft, flown by trained pilots communicating by voice with air traffic controllers on the ground. The system was built around human capacity, supported by radar and radio. Airspace, for decades, was structured around a manageable rhythm of take-offs, landings, and en-route flights.

But in the 21st century, that exclusivity has ended. The skies are no longer the private domain of manned aviation. Thousands of Remotely Piloted Aircraft Systems (RPAS), more commonly known as drones, now populate the airspace. What began as hobbyist tools for aerial photography has rapidly evolved into sophisticated instruments with commercial, humanitarian, and even défense functions. Drones deliver medicines to remote villages, map agricultural fields, monitor forests for illegal logging and fires, and—perhaps soon—carry passengers as prototypes of autonomous air taxis.

This change is transformative, but it also presents a dilemma. The world’s airspace management system—Air Traffic Management (ATM)—was never designed with drones in mind. ATM relies on human pilots in cockpits, voice communication with air traffic controllers, and human judgment in emergencies. Drones, by contrast, are controlled from the ground through digital signals, often far from the aircraft. Any disruption—delays, interference, hacking—can mean immediate loss of control.

The question is therefore not whether drones can be useful. They already are. The real question is how drones can be safely, fairly, and sustainably integrated into an ATM system that was designed for a very different era. And for Indonesia, the world’s largest archipelagic state, the stakes are particularly high.

The Global Context: How Others Are Preparing

Indonesia is not alone in facing the drone challenge. Around the world, governments and industries are testing frameworks to integrate drones into shared airspace. In the United States, NASA and the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) have been testing the Unmanned Aircraft System Traffic Management (UTM) concept. Major tech companies like Google’s Wing and Amazon have trialed drone deliveries in suburban areas, supported by digital traffic systems that let drones file flight plans like manned aircraft. In Europe, the European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) has launched the U-Space initiative, a digital framework to handle the growing number of drones in city environments. Countries such as France, Switzerland, and the Netherlands have experimented with urban drone corridors, where drones fly at designated altitudes while keeping safe distances from helicopters and traditional aircraft. In Japan, policymakers are even more forward-looking. With a plan for urban air mobility by 2030, the Japanese government is preparing not only for drones that deliver parcels but also for those transporting people. The goal is to ease congestion in major cities by allowing fleets of air taxis to fly above city traffic.

The common lesson from these global cases is clear: drone integration is not a matter of whether, but of when and how. Countries that prepare early will shape the standards, rules, and economic opportunities. Those who delay risk becoming passive users of foreign technologies and frameworks.

For Indonesia, with its vast geography, thousands of islands, and uneven infrastructure, drones represent not a luxury but a necessity. The ability to send blood across Papua’s mountains in 30 minutes instead of eight hours by road could literally mean the difference between life and death. The ability to monitor wildfires in Kalimantan in real time could prevent disasters from escalating. The ability to deliver food and medicine quickly to remote islands could transform disaster response.

But these opportunities are meaningless without safe integration into the airspace. Indonesia cannot simply import foreign models wholesale. It must craft a system that reflects its unique realities, both geographic and social.

The Three Technological Pillars of Integration

If drone integration is to succeed, three technological pillars are essential: Detect and Avoid (DAA), Unmanned Aircraft System Traffic Management (UTM), and dedicated communication frequencies.

1. Detect and Avoid (DAA): Giving Drones Eyes

In traditional aviation, safety is based on a simple rule: “see and avoid.” Pilots in cockpits are expected to look out the window, spot potential hazards—such as other aircraft, birds, or balloons—and take evasive action. For drones, which lack human pilots on board, this principle collapses.

DAA is the solution. By combining sensors, mini radars, infrared cameras, and artificial intelligence, drones can “see” obstacles and autonomously manoeuvre around them. Yet DAA raises critical questions. Can sensors reliably distinguish between a large bird and a light aircraft? Can they handle the dense airspace of Jakarta, filled with helicopters, tall buildings, and flocks of pigeons? And who is responsible if a DAA-equipped drone still causes an accident—the operator, the manufacturer, or the regulator?

For Indonesia, localized challenges add complexity. In Papua, the skies are crowded with eagles and birds of paradise. In Central Java, traditional hot-air balloons are often released during festivals. A sensor designed for European or American conditions may misinterpret these as threats or ignore them altogether. Indonesia, therefore, needs localized datasets—unique to tropical skies—to train artificial intelligence systems.

Pilot projects are underway. Mini radars and infrared sensors are being tested, with AI trained to recognize different aerial objects. In the future, Indonesia could build a national database of bird migration patterns, balloon launches, and weather anomalies to ensure DAA reflects local realities.

2. UAS Traffic Management (UTM): Digital ATM for Drones

If DAA gives drones eyes, UTM gives them brains. Unlike a traditional ATM, which relies on human voice communication, UTM is fully digital. Drone operators file digital flight plans, and the system automatically verifies, monitors, and adjusts routes in real time. This makes it possible to manage thousands of drone flights simultaneously—something traditional ATM cannot handle.

But again, questions arise. Should UTM be controlled by governments or outsourced to corporations like Google and Amazon? Should access be equal for all, including small farmers and SMEs, or dominated by large logistics companies? How can UTM and ATM be integrated to ensure drones and manned aircraft share the skies safely? And how can cybersecurity be guaranteed, given that UTM systems will be prime targets for hacking?

Indonesia has begun initial discussions. AirNav Indonesia still manages all airspace, but ministries such as Transportation, Communications, and the National Cyber Agency are debating institutional models. One option is to treat UTM like Indonesia’s national electricity company or central bank: core infrastructure controlled by the state to protect sovereignty, while operational services involve private partners.

Ensuring fairness will also be key. If access fees are too high, small-scale operators will be excluded. A progressive fee system—where large corporations pay more, and SMEs pay less—could preserve inclusivity. UTM portals should also be mobile-friendly, allowing farmers or local cooperatives to register flights easily.

3. Dedicated Frequencies: The Lifeline of Drone Control

Finally, none of the above matters if drones cannot communicate securely. Unlike manned aircraft, which use voice and conventional radio, drones depend entirely on digital frequency channels to connect aircraft and ground stations. Any interference—whether from crowded networks or malicious hacking—can cause immediate loss of control.

The International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) and International Telecommunication Union (ITU) have long called for dedicated spectrum for RPAS. Some countries have allocated experimental channels, but Indonesia still relies on mixed frequencies shared with telecommunications.

The risks are clear. In border areas with Malaysia, Papua New Guinea, or Australia, drones could face interference. Without strong encryption, drones are vulnerable to hijacking. Monitoring spectrum is also a challenge: while the Ministry of Communications monitors telecoms, drone-specific oversight is limited.

Indonesia, therefore, needs a national drone frequency policy: allocating protected channels, establishing a monitoring centre, and ensuring cybersecurity by design. In the long run, bilateral agreements with neighbouring countries will be essential to prevent cross-border interference.

Indonesia’s Unique Challenges

While global lessons are useful, Indonesia’s context brings unique obstacles.

First, infrastructure. Many remote areas, particularly in eastern Indonesia, lack stable internet and communication networks. This makes reliable drone control and monitoring difficult.

Second, law enforcement. Despite regulations, unauthorized drone flights remain common—from hobbyists flying near airports to violations of privacy and restricted zones. Enforcement capacity is limited.

Third, public acceptance. In urban areas, people are not yet accustomed to drones overhead. Concerns about noise, privacy, and safety could grow if hundreds of drones suddenly appear in Jakarta or Surabaya. Without public education, resistance is inevitable.

Opportunities for Indonesia

Yet the opportunities are profound.

- Island logistics: Drones can revolutionize delivery of medicines, food, and essential supplies across thousands of islands, bypassing poor road or sea transport.

- Disaster mitigation: Indonesia is one of the most disaster-prone countries in the world. Drones can provide real-time data during floods, earthquakes, eruptions, and forest fires, saving lives.

- Smart farming: With drones, farmers can map land, monitor crop health, and spray pesticides precisely, improving food security.

- Urban air mobility: In the long run, drone taxis could ease congestion in megacities, offering new mobility solutions.

If Indonesia can overcome its challenges, it could emerge not just as a user but as a regional pioneer in drone technology.

Unresolved Policy Questions

Even with technological pillars in place, policy questions remain unresolved.

- Who is responsible when a drone accident occurs—operator, manufacturer, or regulator?

- How can access to UTM be made inclusive for small players, not just big corporations?

- Can Indonesia push for ASEAN-level drone standards to avoid fragmentation in Southeast Asia?

- How will cybersecurity be guaranteed against hacking or foreign interference?

These are not academic questions. They are practical challenges that must be addressed before Indonesia can fully embrace drones.

A Phased Roadmap

Integration cannot happen overnight. A phased roadmap is realistic.

- Now (0–1 year): Expand pilot projects in Papua and Jakarta, test DAA in tropical conditions, identify spectrum options.

- Next (1–3 years): Mandate mini black boxes for long-range drones, build national UTM infrastructure, apply progressive fees.

- Later (3–5 years): Fully integrate UTM and ATM, harmonize with ICAO standards, and enable commercial drone operations across logistics, medicine, agriculture, and mobility.

Closing Reflection: Indonesia at the Crossroads

The skies of the future will not belong exclusively to manned aircraft. They will be shared spaces, populated by manned and unmanned systems alike. The question is not whether Indonesia will face this future, but whether it will shape it or be shaped by it.

Countries like the US, Europe, and Japan are already moving fast. Indonesia cannot afford to lag. The choice is between building a sovereign, inclusive, and safe drone ecosystem that reflects archipelagic realities—or becoming a passive follower of foreign frameworks.

If Indonesia seizes the moment, drones will not only improve logistics, agriculture, and disaster response but also strengthen sovereignty and innovation. The skies can remain safe, fair, and sustainable for all—if policymakers have the courage and vision to act now.

The revolution in the air has begun. The question is: will Indonesia lead or watch from the sidelines?