A quiet airfield with untapped potential

When people think about Indonesia’s aviation landscape, they usually picture the massive gateways: Soekarno-Hatta in Jakarta, Ngurah Rai in Bali, or Sultan Hasanuddin in Makassar. These are the names that dominate headlines, handle millions of passengers, and symbolize Indonesia’s connectivity with the world.

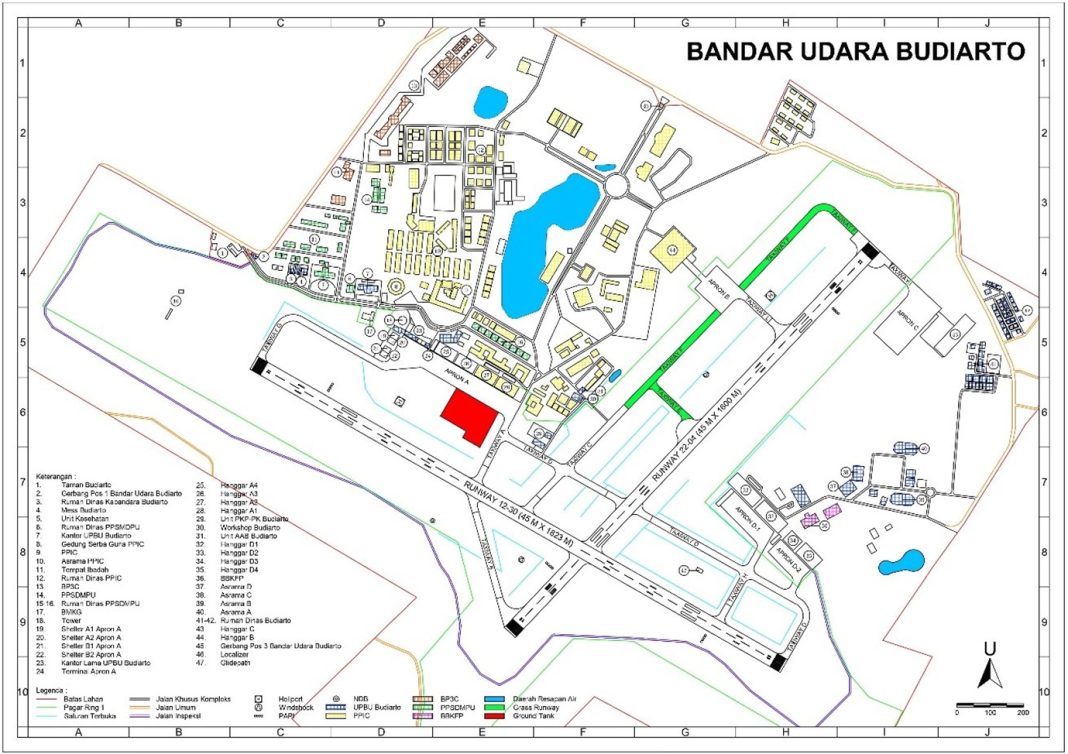

Yet, just a short drive from Jakarta’s heart lies a smaller, quieter facility that rarely enters the conversation—Budiarto Airport in Curug, Tangerang. For decades, Budiarto has lived in the shadows, mostly known as a training field for aviation schools. It was never designed as a commercial hub, and its runways rarely saw anything larger than trainer aircraft.

But this modest airfield is now being reimagined. Through the government’s Kerja Sama Pemanfaatan (KSP) scheme—a public–private partnership model for optimizing underutilized state assets—Budiarto is being positioned for a second life. The vision: to turn idle land into a dynamic hub for general aviation (GA), private jets, and specialized Maintenance, Repair, and Overhaul (MRO) services.

At the core of this transformation lies a fundamental question: is the market ready, and does Budiarto truly have the feasibility to sustain such a future?

From idle land to strategic asset

Indonesia is not short of airports. With over 300 scattered across the archipelago, the challenge is often not about building new runways, but about ensuring existing ones deliver value. Many secondary airports are underutilized, acting more like cost centers than growth engines.

The KSP framework seeks to change that. Instead of letting government-owned land sit idle, it invites private investors to co-develop facilities in ways that generate revenue, jobs, and strategic capabilities. For Budiarto, this means rethinking its role from a sleepy training ground to a specialized cluster supporting GA, private aviation, and MRO.

What makes Budiarto particularly promising is its location. Just outside Jakarta, it is close enough to serve the capital’s immense demand, yet far enough from the congestion of Soekarno-Hatta. Unlike Halim Perdanakusuma—which shares space with the military and suffers from physical limitations—Budiarto still has room to expand. In the land-scarce aviation landscape around Jakarta, that is a golden asset.

General Aviation: Indonesia’s sleeping giant

Globally, General Aviation (GA) is the quiet engine of air mobility. In the United States, GA accounts for nearly 90 percent of civil aviation movements, covering everything from business jets and medevac helicopters to crop-dusting planes and flying schools. Europe too nurtures a strong GA culture, with secondary airports dedicated to light aircraft and training.

Indonesia, by contrast, has long underdeveloped its GA sector. The focus has been overwhelmingly on commercial airlines, understandably so in an archipelagic nation where connectivity is lifeblood. But GA has quietly been growing—spurred by an expanding upper middle class, resource-driven corporations, and a rising appetite for mobility that goes beyond airline schedules.

Here lies Budiarto’s first opportunity. As a dedicated GA hub, it could accommodate flight schools, private owners, and charter operators who currently struggle to find space at Soekarno-Hatta or Halim. For small aircraft, competing with wide-body jets for runway slots is inefficient, if not unsafe. Budiarto offers breathing space, lower costs, and a community environment tailored to GA’s unique needs.

In this sense, the market feasibility is not about whether GA exists in Indonesia—it does—but about whether the ecosystem is allowed to grow. Budiarto, if positioned well, can become the incubator of GA growth in the country.

Private jets: from indulgence to productivity

Private jets have long carried a stigma of elitism. They are often associated with oligarchs and celebrities indulging in luxury travel. But framing them solely as symbols of inequality misses the bigger picture.

In countries with vast geography like Indonesia, private jets are increasingly productive tools. Corporate leaders in mining, energy, or plantations often need to visit multiple sites in a single day. Public airlines, bound by fixed schedules and prone to delays, simply cannot match that flexibility. During the pandemic, when concerns about health and exposure were high, demand for private charters surged.

The Asia-Pacific private aviation market has seen steady growth, and Indonesia is no exception. For such operators, location is key. Budiarto’s proximity to Jakarta makes it convenient for clients, while avoiding the congestion and higher fees of Soekarno-Hatta. With the right facilities—hangars, lounges, security services—Budiarto could become Jakarta’s dedicated private jet hub.

This is a niche market, yes, but it is lucrative. For investors, the ability to tap into high-value corporate customers adds a critical layer to Budiarto’s business case.

MRO: plugging the missing piece

If GA and private jets offer emerging markets, MRO presents an undeniable need. Maintenance, Repair, and Overhaul is the backbone of aviation safety and economics. Yet Indonesia remains heavily dependent on regional neighbours for this critical function. Each year, hundreds of millions of dollars leave the country as operators send aircraft abroad, particularly to Singapore and Malaysia, for servicing.

Garuda Maintenance Facility (GMF) at Soekarno-Hatta handles heavy maintenance for large commercial fleets. But when it comes to small aircraft, business jets, and GA fleets, Indonesia lacks specialized facilities. This is where Budiarto can fill a glaring gap.

With the right investments, Budiarto could host boutique MRO services tailored for GA and business aviation. The captive market already exists—flight schools in Curug, local charter operators, and private owners. Instead of sending their aircraft overseas, they could find services locally at a lower cost. Moreover, with competitive pricing, Budiarto could even attract regional customers, positioning itself as Southeast Asia’s MRO alternative for small and mid-sized aircraft.

In terms of feasibility, MRO represents not just an opportunity but a necessity. Without it, Indonesia will continue to leak value abroad. With it, Budiarto can become a critical node in national self-reliance.

Financial and business considerations

Market feasibility is not just a matter of aviation strategy—it is also a financial question. For Budiarto’s transformation to succeed, the numbers must add up.

Revenue streams: diversification is key. Budiarto cannot rely on a single income source. Instead, a diversified revenue model is needed: leasing hangars, parking fees, MRO contracts, training partnerships, and ancillary services like fuelling, ground handling, and FBO lounges. Each stream might be modest alone, but together they create stability.

Capital expenditure (CapEx). Significant upfront investment is inevitable. Building modern hangars could require IDR 30–50 billion per unit. Runway upgrades, MRO workshops, tooling, and support infrastructure could push total CapEx into the hundreds of billions of rupiah. Such scale demands consortia, patient capital, and potentially blended finance models with government incentives.

Operating expenditure (OpEx). Skilled manpower, compliance costs, utilities, and concession fees will weigh heavily. Cost efficiency is possible through shared services across GA, MRO, and training operators, leveraging Budiarto’s cluster potential.

Cash flow and break-even. Feasibility studies suggest break-even in 6–8 years, though scenarios vary. Optimistic growth in GA and private aviation could accelerate returns to 5 years. A conservative outlook—slower adoption, regulatory delays—may stretch this to 10 years. This underscores the need for investors aligned with long-term horizons.

ROI and IRR. Benchmarks from regional projects show Internal Rates of Return (IRR) of 12–15% as realistic, with positive Net Present Value (NPV) achievable if financing costs are contained. With Indonesia’s rising aviation demand, such returns are attractive if risks are managed.

Accounting and risk management. Under KSP, land remains state-owned, while private partners record improvements as assets during the concession. Depreciation schedules for hangars and MRO tools typically span 15–20 years. Risk provisions must cover warranty liabilities in MRO and currency volatility in spare parts and leases. An enterprise risk management framework is essential.

Public value. Beyond financial metrics, Budiarto’s case is strengthened by non-financial returns: reducing foreign exchange outflow in MRO, producing local talent, creating skilled jobs, and catalysing local industries. These social ROIs justify government facilitation and reinforce investor confidence.

Challenges: turbulence ahead

No project of this scale is without turbulence. Regulatory complexity remains a major hurdle. Aviation development requires coordination across ministries, and delays could dampen investor enthusiasm. Indonesia’s GA base is still small, making growth gradual rather than explosive. Public perception risks framing the airport as an elite playground, unless strong emphasis is placed on training, medevac, and regional service roles. And finally, regional competition is real—Singapore’s Seletar and Malaysia’s Subang already dominate.

But challenges are not deal-breakers. With smart positioning, transparent governance, and proactive communication, they can be managed.

Market feasibility: a narrative, not just numbers

Feasibility studies often reduce opportunities to spreadsheets. But in aviation, feasibility is also narrative. Investors, regulators, and communities must buy into the story.

Budiarto’s narrative is compelling: demand exists, supply is constrained, and strategic fit is evident. The airport is not being reinvented to mimic Soekarno-Hatta or Halim, but to fill a distinct gap. This clarity of purpose matters.

Delivering public value, not just private gain

For Budiarto’s transformation to earn legitimacy, it must show value beyond private profits. Embedding functions like medevac, pilot training, and community engagement will help ensure broader buy-in. Partnerships with PPI Curug and local businesses can strengthen its local anchor. In this way, the airport becomes not just a commercial venture but a public good.

Closing

Budiarto Airport is at an inflection point. Once a sleepy training field, it now has the chance to become a cluster of GA, private aviation, and MRO. Financially, the numbers are challenging but feasible, with IRRs in the mid-teens achievable under the right structure. Strategically, the need is undeniable.

Redefining land utilization at Budiarto is about more than market feasibility. It is a test case for whether Indonesia can turn underutilized state assets into engines of innovation, self-reliance, and public value.

If successful, Budiarto will not just prove its business case—it will set a precedent for aviation development across Indonesia.