1. Introduction: Where Sky Meets Sea in the World’s Largest Archipelago

With over 17,000 islands and a coastline stretching more than 108,000 kilometres, Indonesia possesses a geographic gift — and an operational challenge — unmatched by any other nation. This maritime sprawl makes aviation a necessity, not a luxury. In places where building runways is impractical or ecologically harmful, the answer could be as simple — and as complex — as landing on water.

Seaplanes, or amphibious aircraft, are hardly a novelty. They once connected remote communities in Alaska, the fjords of Norway, and the vast inland waterways of Canada. Today, they form an essential part of tourism economies in the Maldives and Seychelles, and play critical roles in emergency response from Australia’s tropical north to the Caribbean.

In Indonesia, seaplane potential is immense. The natural beauty of Labuan Bajo’s Komodo National Park, the protected waters of Lake Toba, and the bustling bays of Bali could all host amphibious operations that reduce travel time, enhance tourism experiences, and provide life-saving access in emergencies.

Yet in these same waters, life is already busy. Wooden fishing boats weave between anchored yachts, ferries shuttle tourists by the hundreds, dive tenders idle at reef sites, and cargo ships approach harbour mouths. Every vessel moves with its own purpose and schedule — few of which consider the possibility that an aircraft may need to land or take off in the same space.

This is the paradox of the water aerodrome in Indonesia: the most attractive locations for seaplane operations are also the most congested maritime zones. Without a unifying operational framework, every take-off and landing risks becoming an exercise in improvisation.

2. The Operational Challenge

A conventional airport has one advantage a water aerodrome never will: absolute control of its runway environment. On land, a fence keeps intruders out, security ensures compliance, and movements are sequenced down to the minute. On water, there is no fence — and no reason for other users to expect one.

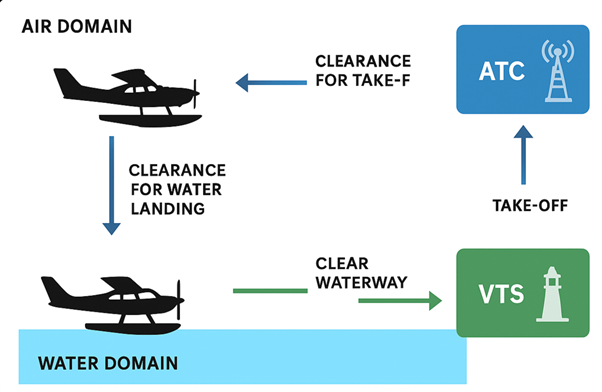

Maritime users operate under the International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea (COLREGs), prioritizing right-of-way rules, safe speeds, and visibility, not timed slot allocations. Aviation users operate under ICAO standards, optimizing for take-off performance, climb gradients, and approach stability, none of which are written with fishing nets or yacht regattas in mind.

Regulatory fragmentation compounds the issue. The Directorate General of Civil Aviation (DGCA) oversees air navigation safety and aerodrome certification under ICAO Annexes 11 and 14. The Directorate General of Sea Transportation (DGST) manages vessel traffic services, port safety, and shipping under IMO conventions. Port authorities, local governments, AirNav Indonesia, and maritime police each hold pieces of the puzzle. Without integration, these pieces do not form a coherent picture.

The operational consequences are tangible:

- Spatial conflicts: vessels entering or crossing seaplane take-off paths.

- Wake hazards: speedboats generating wave energy that destabilizes aircraft hulls during taxi.

- Information gaps: ATC unaware of a slow-moving barge blocking the approach lane; VTS unaware of a seaplane short on fuel requesting expedited landing.

- Jurisdictional delays: unclear authority to instruct or penalize non-compliant users.

Addressing these requires not only coordination but integration — a single operational philosophy where air and sea traffic management are not parallel systems but interlinked ones.

3. The IM-MUT Framework: Three Pillars for Safe and Predictable Operations

The Integrated Management of Mixed-Use Traffic (IM-MUT) model rests on three operational pillars: Zoning, Scheduling, and Information Sharing. Each is reinforced by enabling regulations, institutional arrangements, and technology.

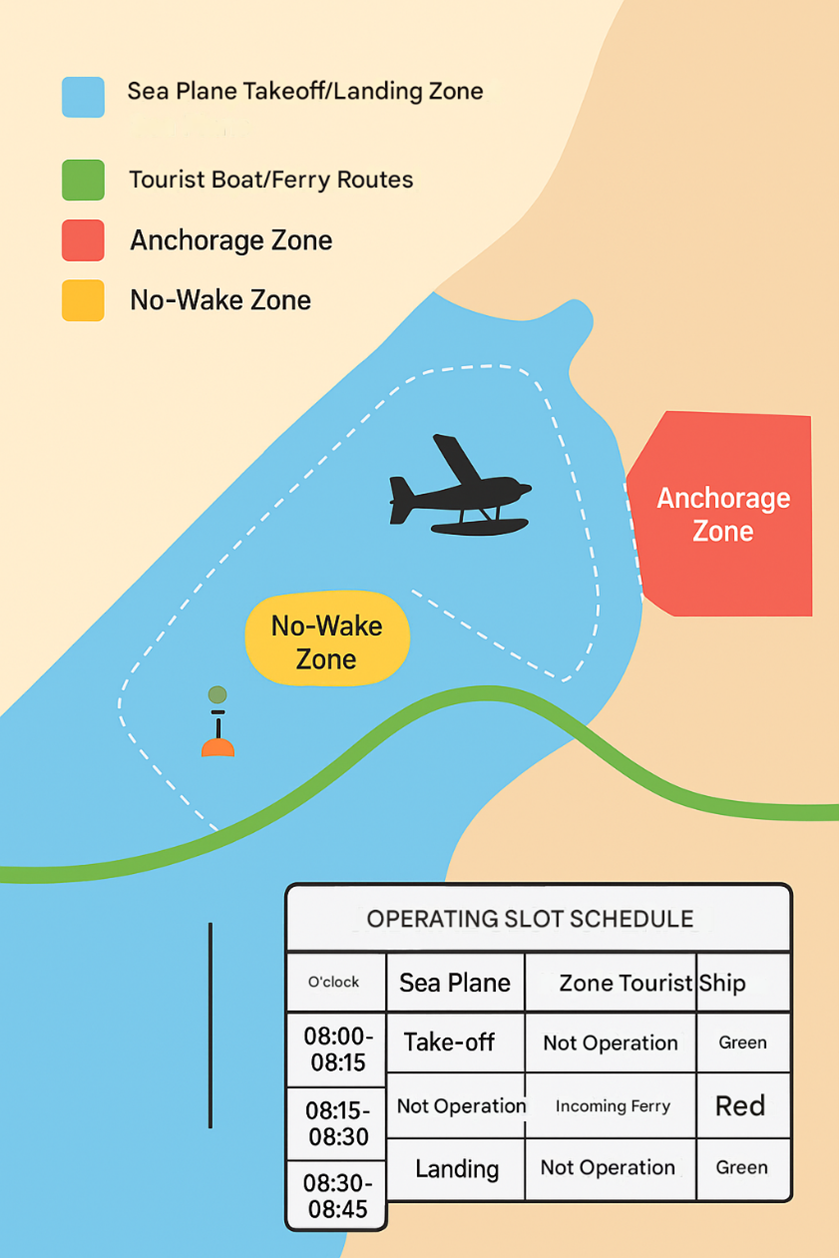

3.1 Zoning: Mapping Operational Space with Surgical Precision

Zoning is the physical foundation. It divides a water aerodrome into clearly defined sectors, each with a purpose, marked both physically and digitally.

- Water Runway/Alighting Area: Length and width determined by aircraft performance data. A DHC-6 Twin Otter on floats typically requires 1,050–1,200 meters at MTOW in calm conditions. Alignments are chosen to optimize wind advantage while avoiding terrain or tall structures in climb-out paths.

- No-Wake Zones: Defined radius around taxi lanes and runway thresholds, enforced with speed limits and penalties. These areas use conspicuous buoys, backed by patrol boats or fixed cameras for monitoring.

- Traffic Separation Schemes (TSS): Borrowed from IMO practice, TSS creates inbound and outbound vessel corridors that do not intersect aircraft approach/departure paths. Any necessary crossings occur at designated points under VTS–ATC coordination.

- Anchorage and Loitering Zones: Locations chosen for deep water, shelter from prevailing seas, and minimal wake propagation toward the runway.

- Emergency Zones: Pre-cleared areas for aborted take-offs, controlled ditching, and SAR boat access, marked in both nautical and aeronautical publications.

- Digital Geofencing: Zoning boundaries encoded into AIS transponders (for vessels) and EFBs (for pilots), generating real-time alerts for unauthorized incursions.

By layering physical, regulatory, and digital barriers, zoning turns open water into a managed operational environment.

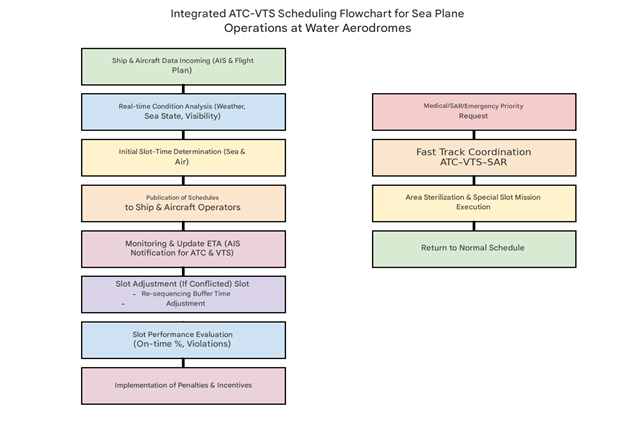

3.2 Scheduling: Orchestrating Time to Prevent Conflict

If zoning manages space, scheduling manages time. The goal is to prevent peak-time overlap of incompatible movements.

- Integrated Slot Systems: Shared software allocates time blocks for seaplane operations and vessel passages through conflict zones. For example, a seaplane take-off window might run from 10:00 to 10:07, followed by a vessel passage window from 10:08 to 10:20.

- Dynamic Adjustments: Slots can expand, contract, or shift based on sea state, wind, visibility, or unplanned events (e.g., emergency landings).

- Pre-Advisory Alerts: AIS-linked ETA updates from large vessels automatically adjust available seaplane slots in the system.

- Priority Protocols: SAR missions, medical flights, and disaster-response aircraft bypass standard sequencing under JSOC authorization.

- Performance Incentives: Operators who maintain schedule discipline receive preferred slot access; repeated violators face lower priority or fines.

3.3 Information Sharing: Building a Common Operational Picture

This is the nervous system of IM-MUT. Without real-time, shared situational awareness, zoning and scheduling lose effectiveness.

- AIS–ADS-B Fusion: Combining maritime and aviation surveillance data into a single display, with conflict prediction algorithms highlighting potential hot spots.

- SWIM–STM Integration: A local adaptation of System-Wide Information Management (SWIM) for aviation and Sea Traffic Management (STM) for maritime. This allows both domains to share route plans, ETAs, status updates, and hazard warnings.

- Unified Communications: Dedicated ATC–VTS voice channels, standardized phraseology, and interoperable radio systems.

- Public Transparency: Publishing operational zones and slot structures in both the AIP and Notice to Mariners ensures all users are informed.

- Audit Trail: Every coordination logged for post-event analysis, feeding into a “just culture” safety loop.

4. Institutional and Regulatory Backbone

A framework is only as strong as the institutions that uphold it. In Indonesia’s case, the IM-MUT concept demands a governance architecture that aligns national regulatory bodies, operational agencies, and local stakeholders without blurring their respective mandates.

4.1 A Dual-Authority Partnership

The natural starting point is a formal Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) between the Directorate General of Civil Aviation (DGCA) and the Directorate General of Sea Transportation (DGST). This MoU would:

- Define shared operational zones and publish them in both the Aeronautical Information Publication (AIP) and the nautical Notice to Mariners.

- Mandate slot-time coordination between ATC and VTS.

- Establish joint enforcement protocols, including authority to issue warnings, levy fines, and detain vessels or suspend flight operations in cases of repeated non-compliance.

- Set the legal basis for data exchange between aviation and maritime systems, addressing privacy, security, and liability.

- 2 The Joint Seaplane Operations Cell (JSOC)

- Operational execution would rest on a JSOC — a co-located unit at each priority water aerodrome bringing together:

- ATC representatives (AirNav Indonesia or DGCA staff)

- VTS controllers (DGST or port authority staff)

- Port and harbourmaster personnel

- Maritime police and SAR units

- Seaplane and vessel operators’ liaison officers

- Local government and tourism authority observers

The JSOC would operate 12–18 hours daily, depending on traffic patterns, with a unified control room, shared radar and AIS–ADS-B displays, and direct voice links. It would be responsible for real-time deconfliction of traffic, emergency coordination, and performance monitoring.

4.3 Regulatory Harmonization

Integration must bridge the gap between two international regimes — ICAO and IMO — and two national regulatory ecosystems. This involves:

- Amending relevant Ministerial Regulations to formally recognize water aerodromes as mixed-use traffic zones subject to joint governance.

- Embedding no-wake and speed-limit rules in maritime law, enforceable under port jurisdiction but also referenced in aerodrome operating procedures.

- Ensuring environmental compliance, such as alignment with marine protected area statutes and environmental impact assessments (AMDAL).

4.4 Funding and Sustainability

Joint governance also means joint funding. Revenue streams could include:

- User charges for seaplane movements and vessel entries to designated zones.

- Public Service Agency (BLU) revenues from DGCA or DGST operations.

- Public–Private Partnerships (PPP) for infrastructure such as buoys, patrol boats, and integrated surveillance systems.

- Donor or CSR grants for environmental protection measures tied to the IM-MUT program.

5. Human Factors and Community Engagement: The People in the System

Technology and regulations can set the stage, but it is people — controllers, pilots, captains, and communities — who deliver safety in practice.

5.1 Cross-Training for Controllers

ATC officers must understand the basics of maritime navigation and COLREGs, while VTS controllers must grasp the operational envelope of amphibious aircraft. Cross-training modules could include:

- Joint simulation exercises in virtual environments combining vessel and aircraft movements.

- On-the-job rotations, where ATC spends shifts in VTS control rooms and vice versa.

- Field familiarization, including ride-alongs on patrol boats and jump-seat observations in seaplanes.

5.2 Building Local Acceptance

In many Indonesian ports, informal maritime traffic patterns are deeply embedded in community life. Sudden imposition of strict zones or speed limits can provoke resistance. The key is early and continuous engagement:

- Consultations with fishermen, ferry operators, and tour boat captains before implementation.

- Community briefings using visual maps and real-world scenarios.

- Incentives for compliance, such as priority docking slots or marketing partnerships for tourism operators.

5.3 Environmental Stewardship

Community support also hinges on protecting the waters they depend on. Measures could include:

- Routing to avoid sensitive coral reefs or seagrass beds.

- Using low-wake approach profiles for seaplanes to minimize shoreline erosion.

- Deploying oil-spill containment kits at seaplane docks.

- Monitoring noise levels and adjusting operating hours to protect local wildlife.

6. Economic and Strategic Value: Beyond Safety

While safety is the non-negotiable foundation, the IM-MUT model’s economic and strategic benefits can be equally compelling.

6.1 Tourism Multiplier

Reliable seaplane operations can significantly increase visitor spending by:

- Expanding same-day connectivity between hubs (e.g., Bali–Labuan Bajo in under 90 minutes).

- Offering scenic flight packages tied to luxury resorts.

- Supporting event-based tourism, such as sailing regattas or cultural festivals, with high-speed access.

6.2 Emergency Response and National Resilience

In a disaster-prone country, amphibious aircraft are invaluable:

- Post-earthquake relief when runways are damaged but harbours remain usable.

- Medical evacuation from remote islands without airstrips.

- Rapid SAR deployment in maritime accidents.

An integrated IM-MUT system ensures these missions are not delayed by uncoordinated traffic.

6.3 Strategic Positioning

Indonesia could become a regional leader in integrated air–sea traffic management, exporting both expertise and technology to other archipelagic nations. This aligns with broader government visions of maritime leadership under the “Poros Maritim Dunia” (Global Maritime Fulcrum) doctrine.

7. Policy Roadmap: From Pilot Projects to National Rollout

7.1 Phase 1 – Foundation (Year 1–2)

- Select three pilot sites: Labuan Bajo, Tanjung Benoa, Lake Toba.

- Establish JSOC units and sign DGCA–DGST MoU.

- Implement basic zoning with buoy markers and AIP/nautical chart publication.

- Begin AIS–ADS-B data integration for situational display.

7.2 Phase 2 – Optimization (Year 3–4)

- Introduce integrated slot allocation software.

- Enforce no-wake zones with patrol and camera monitoring.

- Conduct semi-annual joint simulation exercises.

- Launch public dashboards for zone and slot visibility.

7.3 Phase 3 – Expansion (Year 5+)

- Scale to additional high-potential sites (e.g., Raja Ampat, Belitung).

- Integrate SWIM–STM platforms for richer data sharing.

- Develop an Indonesian Water Aerodrome Regulatory Code consolidating lessons learned.

8. Conclusion

The IM-MUT concept is more than a safety mechanism for seaplanes. It is a national capability that transforms the operational logic of shared maritime and aviation spaces. It recognizes that in Indonesia, water is not just a barrier to be crossed — it is the runway, the taxiway, and the lifeline.

By embedding Zoning for spatial discipline, Scheduling for temporal harmony, and Information Sharing for collective awareness, Indonesia can ensure that the meeting point of sky and sea is one of precision and predictability, not chaos and chance.

The payoff is clear: safer skies and seas, a stronger tourism economy, resilient disaster response, and a reputation as a nation that can lead the world in integrated transport management. In the crowded waters of the future, this will be the difference between missed opportunities and mastered potential.